14th Amendment, Section 1

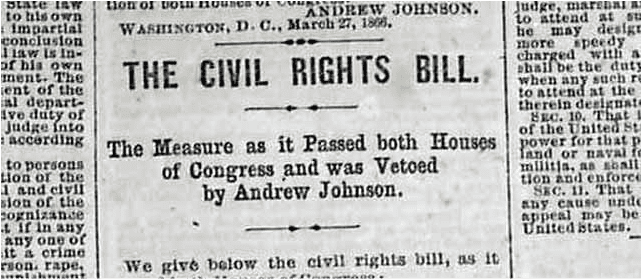

In early 1866, the Joint Committee of Fifteen on Reconstruction in the 39th Congress wrestled with the idea that they must write a 14th Amendment to address certain issues:

Who is a citizen? How does the country’s laws apply to former slaves and slave owners? Will former Confederate officials hold elected office now in the Union? Will former slaveholders receive any compensation for the loss of their property? Who will pay the Confederacy’s debts?

Most importantly, who will rule supreme: state governments or the federal government?

The Joint Committee members wanted an all-encompassing Amendment that addresses each issue because they understood that future Congresses or the courts may disavow the laws that they would write and pass now but an Amendment would make it more or less permanent.

The Joint Committee members argued, debated, negotiated, and compromised, until they submitted to the House and Senate a 14th Amendment that contained five sections.

Section 1 begins: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

Historians have pointed to John Bingham, representative from Ohio and member of the Joint Committee, as primary author of Section 1.

They point out that Bingham’s words in Section 1 unraveled Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Roger Taney’s words when he wrote the Dred Scott decision back in 1857, that black slaves are not citizens, that they never can become citizens, and that they are without any rights.

Taney based his decision on the Constitution, what some call a slave-holding document.

Remember the 3/5’s clause in the Constitution? Southern states received more representation in Congress and in the Electoral College because each slave was counted as 3/5’s of a person. This unfair advantage meant that the Southern states would control the Presidency until Lincoln.

Bingham declared, “All persons born or naturalized in the U.S. are citizens.” That means both black and white, Jew and Gentile, male and female, oldest in the family or youngest. It makes no difference where a person’s parents were born, their religion, or their culture.

Per the 14th Amendment, all are citizens if born here or are naturalized here, Mr. Trump.

Section 1 continues: “No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.”

The words, “No state shall make or enforce any law . . . ,” is a radical change to the first words in the first Amendment in the Bill of Rights, “Congress shall make no law . . . ”

James Madison of Virginia, who wrote the Bill of Rights, feared a too powerful Congress, but the Civil War demonstrated that it was the states that can cause immense damage to the Union.

The words, “No state shall make or enforce any law,” indicates that the Federal government now stands supreme. Bingham pitched aside the Southern states’ ongoing cry for “States Rights.”

What are “the privileges or immunities of citizens?” Bingham believed they were the rights listed within the first 10 Amendments, the Bill of Rights.

Section 1 continues: “nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”

Please note here, Mr. Trump, that Bingham wrote “any person.” He did not write “citizen.” Any person, citizen or foreigner, is entitled to life, liberty, property, and the due process of law.

Akhil Reed Amar, legal scholar at Yale University, pointed out in his book, The Bill of Rights, that Bingham found this idea of extending rights to non-citizens in Exodus 22, in the fourth Commandment. “Remember the Sabbath Day, to keep it holy.” All shall rest on that day.

That includes sons, daughters, manservants, oxen, and “the stranger that is within thy gates.”

Bingham asked, “Are we not committing the terrible enormity of distinguishing here in the laws in respect to life, liberty, and property between the citizen and stranger within your gates?”

Next time in these pages I will continue to unpack ideas out of the 14th Amendment.

Bill Benson, of Sterling, is a dedicated historian.