Roger Williams vs. the Puritans

Roger Williams vs. the Puritans

Last time in these pages, I mentioned Jonathan Winthrop’s “city on a hill” sermon, “that all the eyes of all people are upon us.” Winthrop considered himself a type of Moses who was leading his people, like Israel, to a new land, to build a new Jerusalem.

This is spelled out in John Barry’s 2012 book, “Roger Williams and the Creation of the American Soul: Church, State, and the Birth of Liberty.”

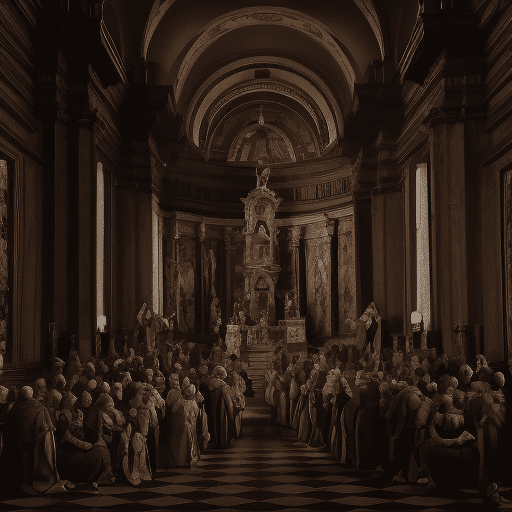

Winthrop and his fellow Puritans believed the city on a hill should have a church and a state, and that the two should work together, like left and right hands. In essence, Winthrop wanted to build a theocracy, in New England, in 1630.

The Puritans expected the magistrates to support the church by compelling people to attend worship, to recite oaths, to pray prescribed prayers, and to tithe.

Those who refused to obey their laws paid fines, were jailed, were locked into stocks, suffered the loss of their ears, were banished back to England, or were hung.

In turn, the clergymen were expected to support the magistrates by providing Biblical justification for dispensing punishment, and by confirming the magistrates’ edicts.

John Barry pointed out that one early Puritan to Boston disagreed with this well-oiled theocratic machine, and that was Roger Williams, an Anglican clergyman, who argued for a freer, more liberated, society.

Roger insisted that a wall should separate church from state, creating two spheres of authority, and that one sphere should not overlap or support the other.

Roger’s view was unique in Massachusetts, in England, in the entire world.

He arrived in Boston in 1631, and right away he stirred up controversy. The Puritans heard him out, but they thought his idea dangerous, that their plantation would fail if they implemented his idea.

He told his fellow Puritans that their government has no authority over the first four Ten Commandments, what he called the First Tablet: no other gods, no graven images, no swearing of oaths, no compelling attendance at worship on a Sabbath.

Those four commandments were private, between God and a man or a woman.

Roger explained that he believed that the state did have authority over the last six, the Second Tablet, because those pertain to human beings’ relationships with others.

Winthrop, the magistrates, and the clergyman in Boston could make no sense of this. Why, they wondered, would he divide the Ten Commandments into two tablets, and expect obedience to the second, but not the first.

Roger urged Massachusetts toward religious freedom, to a free conscience, where all can believe what they want and speak what they believe, without state interference.

A twentieth-century colonial American historian Perry Miller said that Roger Williams is “always there to remind Americans [to] no other conclusion but absolute religious freedom was feasible in this society.”

Out of fear of a loss of their power, the magistrates disagreed, brought Roger to a trial in October of 1635, and voted to banish him from Massachusetts. He fled into the wilderness in January of 1636, and alongside the Narragansett Bay began a new colony.

Rhode Island’s government implemented Roger’s idea, wrote freedom of conscience into its charter. Members of other religious faiths heard the welcome news and poured into the colony: Catholics, atheists, Quakers, Jews, Baptists, and others.

Roger welcomed them all. He disagreed with their religious faith, especially the Quakers, but he permitted them to worship as they wanted in Rhode Island, with no harassment or persecution from Rhode Island’s state government.

John Barry wrote, that then Rhode Island was the freest society in the known world.